Van Halen and the Genius M&M Metric

Remember the 80s? Remember Van Halen? Big hair. Spandex. David Lee Roth’s acrobatic jumps. Brown M&Ms.

Yes, you might remember Van Halen as the M&M divas. These rock stars—David Lee Roth in particular—became known for a contractual clause that began wit h their 1982 World Tour. The press reported that the band would throw a fit whenever the bowl of M&Ms in their dressing room had brown ones in it. A full blown, rock and roll, trash-the-place tantrum. At one Pueblo, Colorado venue, David Lee Roth destroyed his dressing room, kicked a hole in the door, which ended with a itemized damage he called “twelve thousand dollars’ worth of fun.”

h their 1982 World Tour. The press reported that the band would throw a fit whenever the bowl of M&Ms in their dressing room had brown ones in it. A full blown, rock and roll, trash-the-place tantrum. At one Pueblo, Colorado venue, David Lee Roth destroyed his dressing room, kicked a hole in the door, which ended with a itemized damage he called “twelve thousand dollars’ worth of fun.”

It’s true. Partly. Article 126 in the standard Van Halen contract—called a rider—read, “There will be no brown M&Ms in the backstage area, upon pain of forfeiture of the show, with full compensation.”

But there is also a deeper, much more interesting truth.

Van Halen’s shows were among first mega concerts. The stage sets were hugely complex, with intense electrical and structural demands. Mistakes could result in show mishaps, delays, or like the judgment lapse in Pueblo, Colorado regarding the weight tolerances of the stage, facility damage costs of up to $85,000. More than monetary costs, collapsing beams or electrical overloads could hurt people. Back in the early 80s, the typical rock band hauled around three tractor-trailers full of equipment. Van Halen’s concerts required nine tractor trailers. Here’s a typical item in the 53-page rider, just one among hundreds:

“There will be fifteen amperage voltage sockets at twenty-foot spaces, spaced evenly, providing nineteen amperes total, on beams suspended from the ceiling of the venue, which shall be able to support a total gross weight of 5,600 pounds each, and be suspended no less than 30 feet, but no more than 37.5 feet, above the stage surface.”

With so much stuff, how could you ensure the set-up crews, different for each town, read the specs correctly?

Van Halen’s solution was the M&Ms. Buried deep in the rider was the requirement to put a bowl of M&Ms in their dressing rooms… M&Ms with all the brown ones removed. As the band arrived to check the venue, any failure to comply with the M&M rule was a reliable predictor of other mistakes. This would trigger a line-check of the entire production to find the “guaranteed” technical error.

This M&M metric was genius.

© 2010 by Scott M. Brooks. All rights reserved.

Management Science Notes: Top Ten Truths of Employee Turnover

This just in: Job openings rose sharply in January 2010. Employers are cautiously increasing their hiring as the economy improves. While a far cry from signaling the end of the recession, it serves as a reminder that good employees can and will quit.

Here’s a summary what the management sciences tell us about turnover.

- Zero turnover is not the goal – While we don’t like it when employees break up with us, zero turnover is unattainable and also ignores functional turnover. The alternative is “turnover management” – which includes managing costs, transitions, and talent.

- Disengaged people quit – Supported by thousands of academic articles and even more practitioner “12-step” programs, focusing on disengagement is valuable. However mono-focus on this “push” away from organizations can distract us from also attending to the “pull” forces to other opportunities or the “friction” forces that—like switching costs—make it harder for people to leave.

- Everyone’s story is unique – Each person’s specific situation is unique, and there will be no two quitting employees with exactly the same situation. This reinforces the need for continuous dialog with values employees, keeping tabs on their needs.

- There are common “push” patterns that drive people away from an organization – Despite the uniqueness of each situation, recurring patterns deal with low levels of confidence in the leadership or the future of the organization, career opportunities, respect and recognition from one’s manager, sense of personal accomplishment, or… yes… pay. More broadly, people that quit do not see a promising future for themselves within the organization.

- Employees are reasonable, but imperfect judges of the forces leading them to quit – This is the geekiest of the truths, yet one of the most subtle. If you rely only on why quitting employees say they quit, you will over-weight pay and individual managers. Instead, the best scientific studies that examine the leading indicators of turnover highlight the array of issues in #4 above, where the manager and pay have a role, but must be considered within the larger context of influences. Treat employees’ stated reasons for quitting as “color commentary” to the scientifically derived “play by play.”

- Most people believe they could find another job – While arguably, many folks are prone to over-estimating their worth in the marketplace, and this common belief colors the impressions of their current employers.

- Pockets of risk can be identified – It is shockingly easy to track turnover risk, yet so few organizations do it with rigor. Disengaged groups are easy to spot, often “stepchild” groups, those with limited opportunities, or those in poorly defined jobs. More often overlooked, but still easily identified are those more easily “pulled” to other opportunities, often high performers, management, or jobs with a particular marketplace demand.

- Not all turnover is equal – As much as it grates against our democratic HR spirit, while all employees are equally deserving of human respect and dignity, not all employees are of equal value to the organization. Pivotal job types, costly to replace individuals, high performing or high potential employees should be more closely monitored to identify and preemptively address turnover risk. Many organizations track turnover rates. Not many track turnover rates separately for these kinds of special segments.

- You can make a difference – Turnover is a business issue to be managed, without subscribing to a fix-of-the-day. Basic solutions will address setting realistic expectations for employees, providing desirable work environments where employees can do what they came to do, and demonstrating respect and a promising future. Balance efforts to address all three forces of turnover: the push (disengagement), the pull (opportunities elsewhere), and friction (switching costs).

- The Goal: build, maintain organizational competence – The goal is not willy nilly minimization of quitting. Manage the flow of talent as a system, not simply a collection of individuals. Set goals. Measure. Develop back-up plans for the undesirable loss of talent. Work backwards from the strategic need.

** A special note on the role of a manager. It’s common wisdom in many circles that people join organizations, yet quit managers. Certainly, anecdotes that support this assertion are easy to find. However, in any room of 20-30 people, ask for a show of hands of how many people quit their last job primarily because of their manager. Those folks will be in the distinct minority. The manager has a role, certainly, but blaming bad bosses can distract our attentions from deeper, more systemic leadership or organizational issues.

© 2010 by Scott M. Brooks. All rights reserved.

Do Something Audacious

Sure. Why not. But what really is the way things work around here?

A health care organization, already with a strong orientation toward patient care and service, came up with a simple plan to demonstrate what’s important. No posters. No performance appraisal redesign. It was a small idea, executed in a big way. This became known as the “Blitz Day.”

The afternoon before the Day, a relatively small set of ambassadors met to get trained and poised for their duties. Early the next morning, they fanned out across the state to all the facilities owned or operated by this organization. There, they went up to any employee they saw, earnestly greeted each individually, and gave that person a card and a piece of candy. The card instructed each nurse, lab tech, clerk… everyone… to think of one idea to improve patient care or customer service and then share it with their manager. The ambassador then moved on to the next employee. And the next. They didn’t try to do too much, and kept their task focused.

To this day, this organization insists that these ambassadors greeted every single one of the thousands and thousands of employees who came to work that day.

Peel apart this deceptively simple task. When one employee voices a great idea for change, maybe some sort of enhancement gets discussed. If listened to, that employee will feel pretty good, like he or she is making an impact. If the idea has merit and is implemented, the workplace improves.

But what if, in one single day, employees across an entire organization are encouraged to talk with their managers to share ideas and think about customers? A buzz develops. Employees talk not just with their managers, but each other. Sharing ideas becomes the norm. Years later, employees will say, “Remember that Blitz Day?” This is how cultural movements can start.

My favorite notion of organizational culture is that it is defined through the stories employees tell. This clearly suggests that effective culture change is achieved by changing those stories.

There is a clear implication: Don’t simply give employees scripts for new ones they should tell. Create events that inspire employees to make up their own stories about what their work means.

© 2010 by Scott M. Brooks. All rights reserved.

Visit www.orgvitality.com

Management Science Notes: What would CEOs claim as their biggest leadership challenge?

Question:

How many organizations engage in succession planning?

Answer:

Most claim to, but only 2/3 of larger organizations really roll up their sleeves.

Some stats…

- Among companies with more than 10,000 workers, 86% reported having a succession plan in place and 69% conduct regular talent reviews. Among companies with less than 10,000 employees, 45% have a formal plan or conduct talent reviews. (i4cp and HR.com, 2008)

- Other studies suggest only 2/3 even have a plan—formal or informal. According to a 2006 SHRM study of 2,406 organizations, only 29% have a succession plan in place, 29% have an informal plan in place, 26% have no plan but intend to develop one, and 16% have no plan and no intention of developing one.

A brief characterization of the reality:

1. Literally ¾ of CEOs claim “succession planning” was the most significant challenge for the future.

- Additionally, about 70% of CEOs said the next most pressing problems were, “Providing leaders with the skills they need to be successful” and “recruiting and selecting talented employees.” (Based on SHRM Foundation (2007) study of 526 C-suite executives in global as well as domestic firms of all sizes)

2. The shape of the workforce will need to change. Among other things, Baby Boomer generations in many countries will force change:

- In the US over the next five years, Baby Boomers (1945-1960) are retiring in large numbers and Generation Y or Millenials (1970-2000) are entering the workforce in much fewer numbers.

- Only 47 million Millenials stand ready to replace the 76 million Baby Boomers now facing retirement.

3. Hiring from the outside may not always be the answer

- 66% of senior managers hired from the outside usually fail within the first 18 months (Center for Creative Leadership).

4. But we may not always have confidence promoting from within without significant skill enhancements

- Only 24% of organizations are confident in their ability to staff leadership positions during the next five years (Watson Wyatt).

- 84% predict that leaders with significantly different skill sets will be required to fill vacant positions (Watson-Wyatt).

5. Some organizations are better positioned than others to leverage talent as a differentiator.

- In companies that foresee no additional layoffs, 60% of executives plan to increase programs for developing high-potential employees (Deloitte).

- In companies that plan still more cutbacks in the coming quarter, just 34% of executives plan to increase high-potential programs (Deloitte).

This prompts a key question: How do our HR priorities align with this characterization of reality?

OrgStories Shorts: Group Presentation Advice with an Edge

Here is a recent post by venture capitalist Mark Suster, giving advice on presenting and story-telling to large audiences: How to Not Suck at a Group Presentation.

OrgStories Shorts are interspersed between OrgStories posts, sharing miscellany related to story-telling in organizational settings.

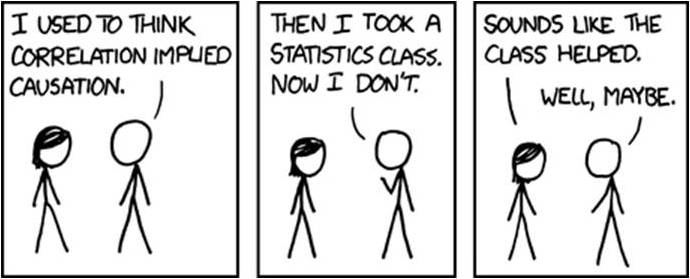

Management Science Note: Nerd Comic

Management Science Notes are interspersed between OrgStories posts, highlighting important research, stats, or scientific concepts relevant to the world of organizational effectiveness.

I Want a Clean Fight (aka Formal Communications Vs. Day-to-Day Realities)

A client of mine struggled to work through a cultural shift, involving a merger, restructuring, “lean” inspired cost cutting, and redefinitions of their target markets… the works. Reasonably, the leadership wanted to clearly communicate the new vision driving all these changes. So through some excellent work by Corporate Communications, a very well-written 20-page document was produced which articulated the need to change, the new directions, and the key values upon which the executives made their decisions.

A client of mine struggled to work through a cultural shift, involving a merger, restructuring, “lean” inspired cost cutting, and redefinitions of their target markets… the works. Reasonably, the leadership wanted to clearly communicate the new vision driving all these changes. So through some excellent work by Corporate Communications, a very well-written 20-page document was produced which articulated the need to change, the new directions, and the key values upon which the executives made their decisions.

It didn’t work.

Virtually no one read it. Those that did felt it was over-produced and typical “executive speak,” providing no real useful information.

One fatal flaw was that this document had very little to do with the day-to-day reality of employees. If you asked them, they would say that the changes taking place in their jobs were:

- Centralization of service delivery, taking away from many field employees the human “touch” they have enjoyed with their customers… often for more than a decade.

- Reduction in the variety of products and services offered, taking away choices that many customers have typically valued.

- Refocusing on some customers to the exclusion of some long-term relationships.

That may sound familiar and recent to many, though I guarantee that it happened a long time ago in an organization far, far away.

So what happened?

Based on the inspiration of one particular executive, this financial services organization realized that it could reconcile the multi-colored, glossy and very “corporate” document about its values with these three realities in one elegant sentence.

They came to say, “We are here for the ages.”

The leaders wanted that. Employees wanted that. Customers wanted that. And phrasing it this way made it easier to demonstrate that the leadership’s decisions (which often frustrated employees) were designed to increase fiscal responsibility, reduce risk, and honor customers’ long-term financial needs.

OrgStories blog launches!

OrgStories is a blog about how organizations function, true to life, and told in bite-sized chunks. Interspersed are Management Science Notes – useful nuggets distilled from the vast and complex domain of organizational research.